Starting Position

I fully admit to being a “carbon (credit) system” novice and my scepticism of the 28,000 carbon credits issued by Recommerce1 was perhaps naive opinion. That scepticism stemmed from a belief that during the life-cycle of a device, carbon is only ever emitted. However, I accept there are two points of potential carbon savings open for discussion. The first is when a consumer opts to buy a refurbished device instead of a new device. The second is if the manufacturer uses parts / materials reclaimed from a device over acquiring new raw materials. Apparently, both are examples of “avoided” carbon emissions.

However, both are hypothetical situations and extremely difficult, if not impossible, to measure/prove. When I purchased my last phone (refurbished iPhone12), was 77 kgCO2e2 actually avoided because a new device wasn’t manufactured? I have no idea. So, with best efforts, I’ve spent some time trying to improve my understanding and develop my thinking and, in an attempt to look behind the headline, here’s how I organised a can of worms.

Understanding “Avoided Carbon”

I struggled to find any standard definition of “avoided carbon” or such like. The IFRS and EU have definitions34 of a “carbon credit” and both include emission reduction as well as removal. I assume in order to end up at “avoided carbon”, someone, at some point, must have interpreted reduction to include scenarios like:

Emissions that would have occurred in "business-as-usual" processes but didn't due to a specific intervention.

The difference between baseline emissions and actual emissions after implementing a specific project or process.

Actions that prevent the release of greenhouse gases (GHG) compared to a reference scenario.

Whatever the interpretation, there are fundamental issues with the concept:

No carbon is being removed from the system, it’s just being monetised.

It’s based on hypothetical scenarios i.e. what would have happened.

It relies on a belief that the emission reduction would not have happened without the specific intervention.

It assumes some level of causation, in that the avoided carbon actually drives change, my iPhone12 example.

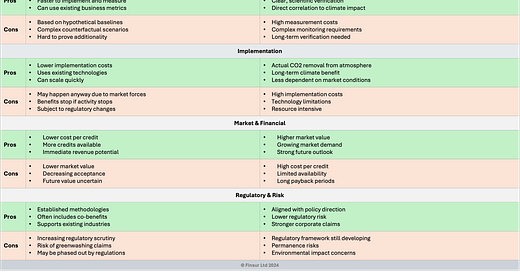

For a novice, it’s not been easy to find objective sources of information, especially after the Verra rainforest scandal5. I used the following table to summarise the pros and cons of Avoidance Credits and Removal Credits, albeit at a high level.

It’s clear there are also issues with removal credits and perhaps comparisons between the two approaches are worthless, or at least a waste of valuable of time6. If you do overcome the ideological and practical challenges associated with issuing avoidance-based carbon credits, finding a market for them may present another set of problems, if not now, certainly in the future.

Studies cited by the UK government point to an overestimation of emission avoidance and reduction7 and new EU rules8 set to ban “greenwashing” based on emission offsetting schemes, amongst other things, will come into force in 2026. Additionally, the latest version of SBTi’s Net Zero Standard states that: “companies should publicly disclose carbon credits which are sourced from outside the company’s value chain (i.e., often referred to as "offset credits") separately from their reported GHG inventory and ensure that they are not counted towards the progress of their science-based targets.”9.

I think this means that the quality of the carbon credit, whilst already important, is likely to come under increasing scrutiny, as are the standards against which credits are produced and verified.

Navigating Standards

Current standards for carbon credit production include: Verra, the largest standard by market share; Gold Standard, founded by the WWF and other NGOs; the American Carbon Registry, an early private registry; Climate Action Reserve, another with North American focus; Plan Vivo, focused on nature-based solutions and; the Global Carbon Council, established in Doha, Qatar.

This exercise was not intended select a standard, but one consideration is likely to be if there’s an existing methodology for the type of project being undertaken. Some organisations also accept projects using methodologies from other approved GHG programmes. If a suitable methodology doesn’t exist, standards organisations accept methodology concepts for ideation, development, review and approval.

Trying to compare the quality of credits produced by different standards organisations is another challenge. Several frameworks exist including the ICVCM, CCQI and VCMI, but they either: rely on projects to be self-submitted for another layer of quality checking; don’t have a wide range of methodologies covered, or focus on the Voluntary Carbon Market itself as opposed to an individual project’s carbon credit quality.

Interestingly, it appears that a “Methodology for Avoiding Carbon Emissions through Refurbishment and Reuse of Electronic Gadgets” was submitted to Verra and subsequently rejected in March 2023 based on “low climate change potential and technical inconsistencies that were not satisfactorily addressed.”10. Further details are not available. Outside of this, Gold Standard list a methodology for the “Recovery and recycling of materials from E-waste”11 . I found no similar methodologies on the other standards organisations’ web sites.

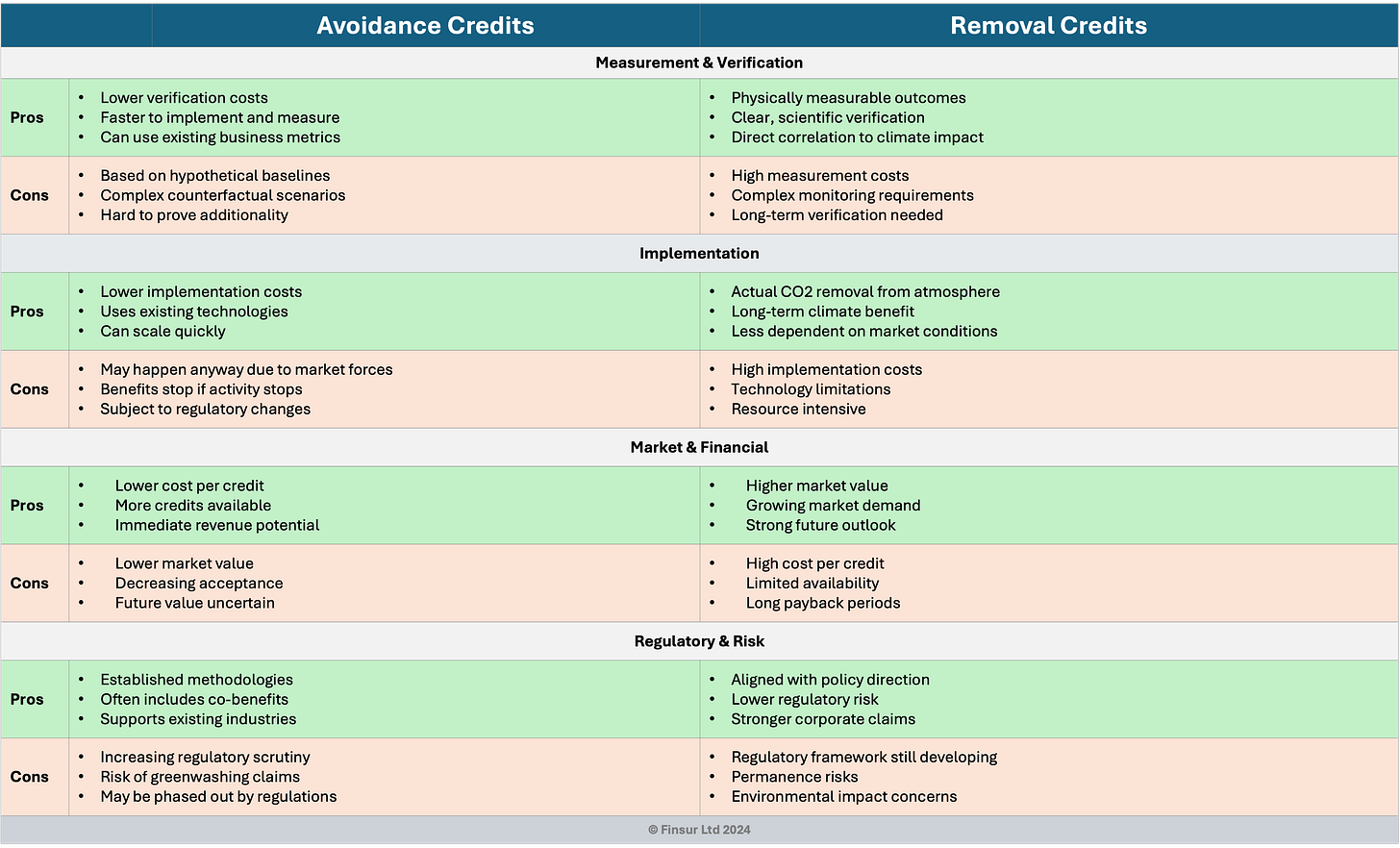

The Recommerce credits were issued by Riverse, a smaller standards organisation that appear to have the only published methodology for the “Refurbishing of Electronic Devices”. They have established a number of projects in the sector. The Riverse standard is endorsed by ICROA12 and they comply with the ICVCM Core Carbon Principles. Verifavia act as the validation and verification body for the projects. There appear to be plenty of checks and balances.

Examining Current Sector Projects

Before the Recommerce announcement finally got me digging, the general topic of carbon offsetting gained attention when Alchemy, in collaboration with carbon accounting firm Greenly, announced in March 2024 they were the only refurbisher able to certify CO2e of devices13. Assurant claimed something similar in September 202314.

According to the public Riverse registry, there are ten similar projects at various stages, all using the E-REFURB methodology and the avoidance mechanism. Three projects have been registered, including two by Alchemy, but no documentation is available yet and the latest entry, by Printerrea, is related to battery refurbishment. Seven projects have been certified with a total of 56,179 carbon credits issued:

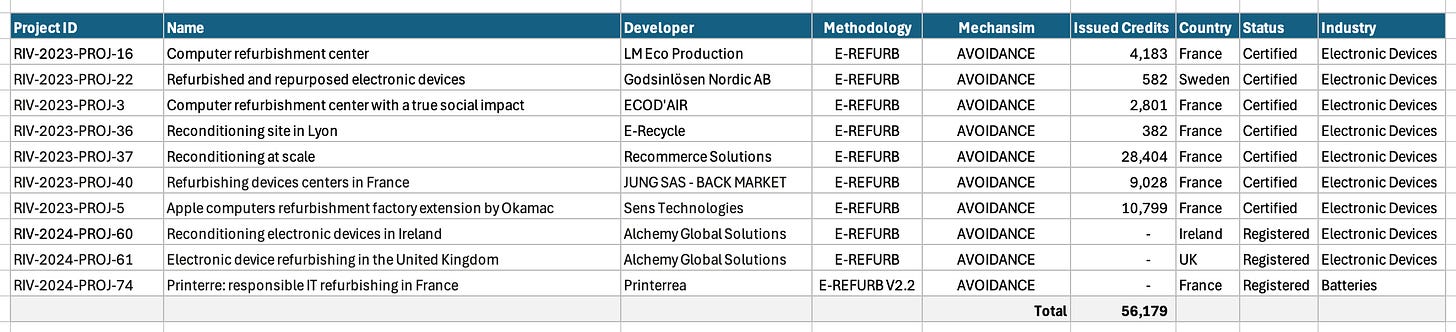

The E-REFURB methodology includes a number of critical assumptions:

Substitution effect & market share: each refurbished device directly avoids the fractional production of a new device based on current market shares (e.g. 0.87 new smartphones for each refurbished one).

Device lifetimes & performance equivalence: refurbished devices provide equivalent service but for a shorter period (e.g. 2 years vs 3 years for smartphones).

Baseline scenario construction: without refurbishment, devices would follow national WEEE collection/recycling rates and be replaced with new devices.

The methodology tries to be conservative (e.g., market share adjustment, lifetime ratios), but the assumptions look vulnerable. For example, the substitution effect assumption seems problematic when compared against the latest emissions data in Apple’s iPhone 16 Product Environmental Report15:

Current Methodology:

Assumes each refurbished device avoids 0.87 new devices (for smartphones)

Uses ADEME study emission factors (84 kgCO2e for new smartphone)

Results in claimed avoidance of ~77 kgCO2e per refurbished phone (after adjustment)

iPhone 16 128GB:

Latest iPhone 16 128GB has verified 56 kgCO2e total product footprint

Applying methodology's own adjustments:

Market share (x0.87) = 48.7 kgCO2e

Lifetime ratio (x2/3) = 32.5 kgCO2e

Minus refurbishment emissions (~7 kgCO2e)

Net reduction = ~25.5 kgCO2e per phone

If I’ve got my sums correct this reveals, even with the conservative approach and the built in buffer, the methodology can become outdated quickly and unintentionally inflate savings as manufacturing processes improve.

Using a three-year primary ownership period in the device lifetime assumption is also open to question. The more common view now is that the initial use phase is currently 3.5 years. What if they head to five?

The 3.5yr scenario reduces credits by nearly 4,000 tonnes and the 5yr scenario reduces credits by almost 11,000 tonnes. In percentage terms that’s -16.8% and -46.8% exceeding the project buffer.

Picking holes in every assumption is perhaps unfair, but these examples have demonstrated, to me at least, that the methodology exposes some fundamental questions. I must add though, in their defence and to their credit, Riverse appear to be continually improving and evolving the E-REFURB methodology16.

There’s much to go after: like replacing the ADEME data set with something more up to date and possibly dynamic that’s closer to the credit issuance date; moving away from a simple percentage buffer and applying different risk rates to different assumptions; addressing the potential for double counting (e.g. previously offset devices) or the risk of multiple parties claiming the same emission reduction; deeper consideration of the cross-border trade implications and regional WEEE regulations and; so on.

Conclusion

A few days worth of study hasn’t elevated my knowledge much beyond complete novice. I’ve got more questions than I started with and I have found areas of complexity that small to medium sized businesses could probably do without. There are clear challenges with the concept of “avoided carbon”, there are too many questionable assumptions in the applied methodology and there is an increasing regulatory burden that will require cost and significant expertise to navigate.

There might be reasons to issue carbon credits: allowing others to participate in the circular economy; supplementary revenue streams; marketing angles; fomo; kudos; etc. But, the circular economy is growing and developing the consumer electronics sector within that seems contributory within and of itself. My thought after this exercise is to start with the carbon mitigation hierarchy17, and focus on reducing your own emissions and supporting others in your value chains to do the same.

I appreciate the intellectual and practical effort involved in creating these incredibly complicated issuance projects, there’s a significant amount of time and expertise being applied in an emerging field, that is clear. However, there are still too many questionable critical assumptions to make the story work for me.

I remain sceptical, just a bit less naive.

Peace.

sb.

Additional Reading:

https://sustainability.freshfields.com/post/102jfym/voluntary-carbon-credits-a-regulatory-grey-area-in-the-eu-part-i

https://files.wri.org/d8/s3fs-public/estimating-and-reporting-comparative-emissions-impacts-products_0.pdf

https://carbonmarketwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/PCG_CMW_rating_agencies_final_report_.pdf

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/internationaldevelopment/2023/01/26/the-verra-scandal-explained-why-avoided-deforestation-credits-are-hazardous/

This is value for smartphones that Recommerce use in their baseline calculation for the 28,000 carbon credits. It’s taken from the 2020 ADEME publication, Page 157 here: https://librairie.ademe.fr/economie-circulaire-et-dechets/5241-evaluation-de-l-impact-environnemental-d-un-ensemble-de-produits-reconditionnes.html